Posted: June 20, 2022

I love stories. As an avid reader of books and watcher of TV and movies, the thing I absolutely love it when a story gives you clues. It’s something that differentiates the good stories from the great ones. It makes a book worth rereading because you know that there will always be something you missed the first (second, third, or even tenth) time around.

This, however, is difficult to do as a writer. It’s just another thing you have to think about while you already have the burden of making the story enjoyable to read. On top of that, your hints may be so obscure that people don’t see them unless you point them out. (But I think that’s half the fun.)

In my opinion, the first step to good storytelling is for your plot to make logical sense—specific to your genre, of course. Children’s stories are a lot looser in logic than an adult mystery thriller, per se. The way I like to ensure that everything makes sense is to lay out my story in its base stages. It’s an extension of how I write as well, so it works doubly for me, and I’ve seen it work for others in the past.

Definitions: A Planner writer typically creates an outline, does research ahead of time, and makes sure they know exactly what the story will be before writing. A Panster writer does little to no planning, and they will sit down and start writing the story “by the seat of their pants”. A Planster writer is a mix of both, and will often write a general outline, but will still go into writing their story somewhat blind.

You’ll want to start out with a single sentence that describes the entire story. What is the thing that happens? Include elements such as who your main character is, where they start, what happens to trigger the story, and where they end up. For example: “Percy Jackson was just another twelve-year-old kid at boarding school, until one field trip, his math teacher transforms into a ravenous monster, and he is sent off on a quest to clear the name of the father he’s never known.” There are many ways to write this sort of sentence, this being one of them, so don’t worry if your own story’s sentence doesn’t work right away. You can always revise it later as you get a clearer image of what your story will be.

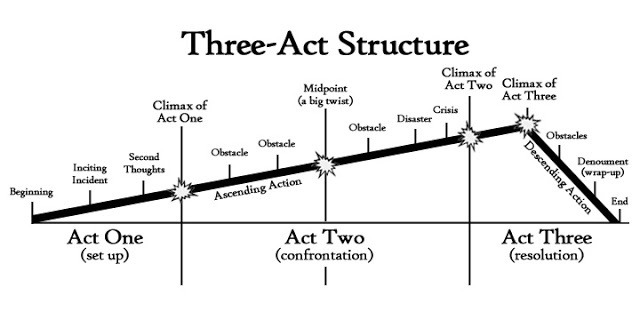

The next step, in my opinion, is to lay out the main plot points of your story to show the progression. What happens to kickstart the story? What events, big or small, happen throughout the story to lead the characters to the big ending? What is the ending? These questions can be answered more easily if you use the three-arc story structure [see below]. Try to be precise and minimal at first; you can fill in other blanks later.

From here, your plot should be easier to understand. You’ll be able to see where the disconnects are if anything doesn’t make sense, and revise as you go. Most people will begin writing at this point. If that’s you, great! I’m a little different.

Speaking solely as a writer, I think of myself as an intense planner. I like being concise, so my method of writing is different than that of people who write as much as they can before cutting back. I work in the opposite direction. Once I have my base points laid out, I will add more detail. I like to have every event planned so that once I finally go through to write the scenes (comprehensive narration and dialogue), I don’t have to worry about where it’s going to go next. All I have to worry about is making it sound interesting.

What’s more, I find it a strategic method for hinting at future scenes.

Since I already know everything that’s going to happen as I’m writing, I can add lines of dialogue or clues in the narration that come back later. I’m going to compare it to writing fanfiction because that is where I have practiced my writing the most. In fanfiction, you’ve typically watched the entirety of a TV show or movie, or read an entire book series before getting into a fandom. Say you’re writing a story about a TV show, but you’ve only watched season one. Your story will reflect that. Then, you watch the second season, or even the third or fourth, and you—as the viewer—receive new information about a character’s backstory that makes you think “oh, that makes so much sense” meaning the character’s actions are better explained. This is because while you don’t know these details in season one, it’s safe to assume that the character knows them. It’s who they are, after all. Armed with these new details, you can much more accurately write a character even if your fanfiction is set during season one without those specific spoilers.

I hope that analogy makes sense for non-fanfiction writers out there.

This carries over into writing your own original work as well. You, the author, know your characters, and if you do the work ahead of time, you can portray your characters much more accurately. If one character has a mystery father who you reveal later, it’s much more satisfying if a reader can go back and reread to find hidden details that point in that direction. And remember, a reader being able to put the clues together ahead of time doesn’t make the reveal any less amazing if you’ve done the clues correctly. (For example Dabi from My Hero Academia)

The easiest example I can use is Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Sorcerer’s Stone for Americans), and the [spoiler alert!] reveal of Quirrell at the end of the book. Now, before I go further, I’d like to say that while I am using this book as an example, I do not approve of any of the hateful messages the author is putting out into the world. Okay, now moving on…

It is revealed at the end of the book that “poor, stuttering Professor Quirrell” was the bad guy throughout the entire story, the one who is working for Voldemort and trying to steal the stone. Throughout the book, we are led to believe that Professor Snape is the evil one as we are reading through the perspective of Harry, who sees the Head of Slytherin House as more intimidating than the easily frightened Defence professor with the perpetual stutter. However, there are subtle clues throughout the story that hint toward Quirrell being the bad guy from the beginning—clues that you only seem to notice the second or third time through (or maybe you don’t even notice until they’re pointed out to you!). To keep things simple and accurate, I will be using the official resource, the Wizarding World website, for this list. I will try to keep things in chronological order. Also note that some of these items wouldn’t scream “evil” so much as they tell us that something isn’t quite right about the character.

These are most of the hints we get of his true nature throughout the book, and it’s still a surprise at the end when the truth is revealed. This is in part because of how effective Snape is as a red herring, but doubly so because of the way the book is written. It’s from the perspective of an eleven-year-old boy, and so in the narration, Harry comes to conclusions that we take into account because it just seems to make sense. We instinctively write Quirrell off as a timid, mostly useless man with no possibility of being evil while Snape is a much more competent bully.

I hope this helps you look more critically at your own stories, and I wish you luck in your writing!

Writing Good Characters

Writing Compelling Villains

How to Do Book Research

D&D Alignments for Writing Characters

Pixar’s 22 Storytelling Rules

Writer’s Burnout Part 1—Explanation & Prevention

Writer’s Burnout Part 2—Identifying Signs & Recovery

Writer’s Block & How to Overcome It

Inclusive Writing

Tigerpetal Press is a small book press dedicated to publishing local authors and poets.